Building for Life 12 has been updated and changed its name to Building for a Healthy Life (BHL). The change came shortly after Covid-19 emerged in the UK and has managed to consider the impacts of the pandemic on good design principles. However, with the pandemic continuing to unfold, its lasting effect on good design remains uncertain. It is clear though that Building for a Healthy Life shows a greater emphasis on cycling and walking. This is likely to be one of a number of changes to persist in the long-term.

Known as England’s most widely used design tool for creating places that are better for people and nature. Building for Life 12’s original 12 point structure and underlying principles remain unchanged. Why change the name, I hear you ask? The new name reflects changes in legislation, as well as the refinements made to the 12 considerations. It is also in response to good practice and user feedback.

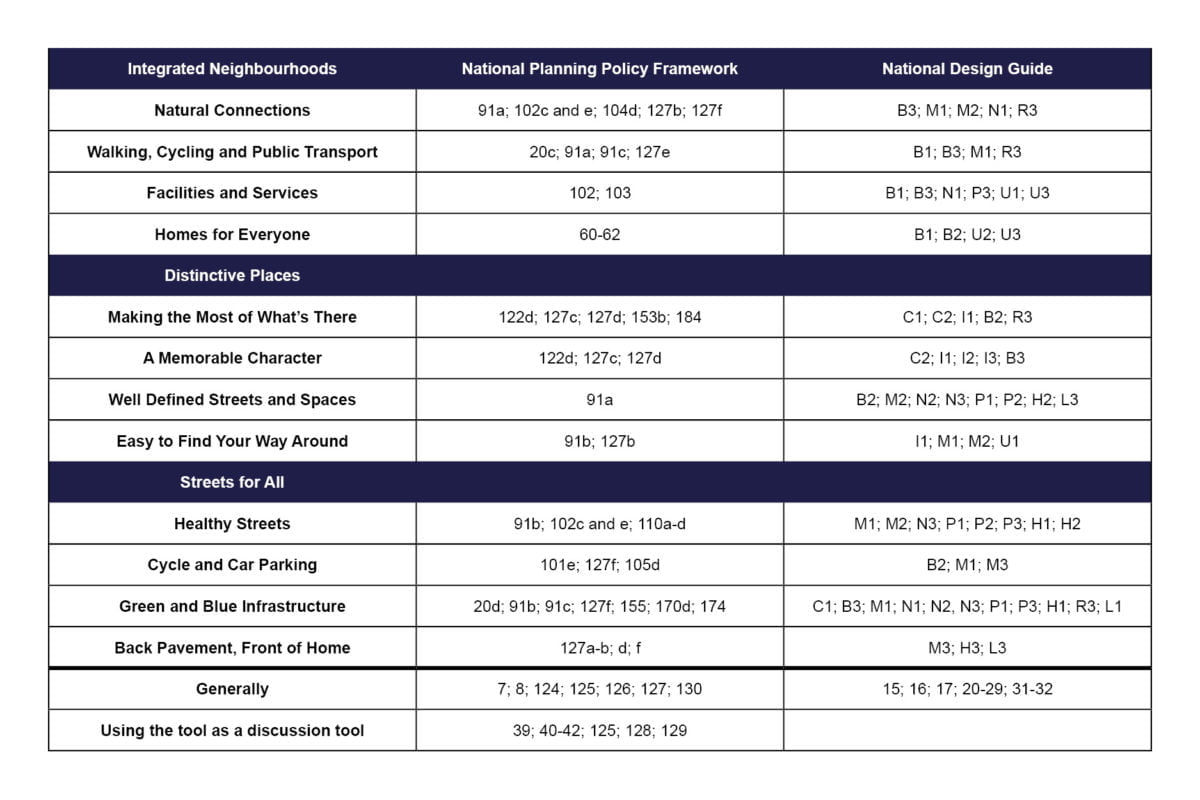

The new name also recognises that this latest edition has been written in partnership with Homes England, NHS England and NHS Improvement. It also integrates the findings from the three-year Healthy New Towns Programme led by NHS England and NHS Improvement. Split into three categories, the 12 considerations all relate directly to the National Planning Policy Framework and the National Design Guide.

Judged against these 12 considerations, a traffic light system will score any new schemes. In this case, an amber light signifies an aspect of the design which may require further resolution. Whereas, a scheme that gets at least 9 green lights and no red lights, can receive a Building for a Healthy Life commendation. This also allows a scheme to use the BHL logo, to recognise its status.

Intended as a tool, Building for a Healthy Life is a guide for the design process. It will be most effective when local authorities and developers can discuss the 12 considerations early in the design process. This will help define how best to achieve a green light against each consideration and to set a framework for engagement with local communities.

Many local authorities across the country may have already cited Building for Life 12 in their Local Plans and Supplementary Planning Documents. As BHL is the new name for Building for Life 12, local authorities will be relieved that they can continue to use BHL, without having to rewrite existing policy documents.

One of the main differences between the editions, is the wording. The 12 headings previously phrased as questions, now are presented as considerations, for example:

“Does the scheme have good access to public transport to help reduce car dependency?” (Building for Life 12)

“Short trips of up to three miles can be easily made on foot or bicycle if the right infrastructure is in place, helping to improve public health and air quality whilst also reducing local congestion and carbon emissions.” (BHL)

It was deemed: “questions demand a quick response whereas good design requires more time, analysis and thought”, which can only be considered as a positive move.

TEP already utilises Building for Life 12 as part of our process for developing urban design and masterplanning projects. To ensure we remain at the forefront of change, we are committed to using Building for a Healthy Life. We also continue to deliver innovative solutions to every design challenge.

To read more from TEP’s design team, click here.